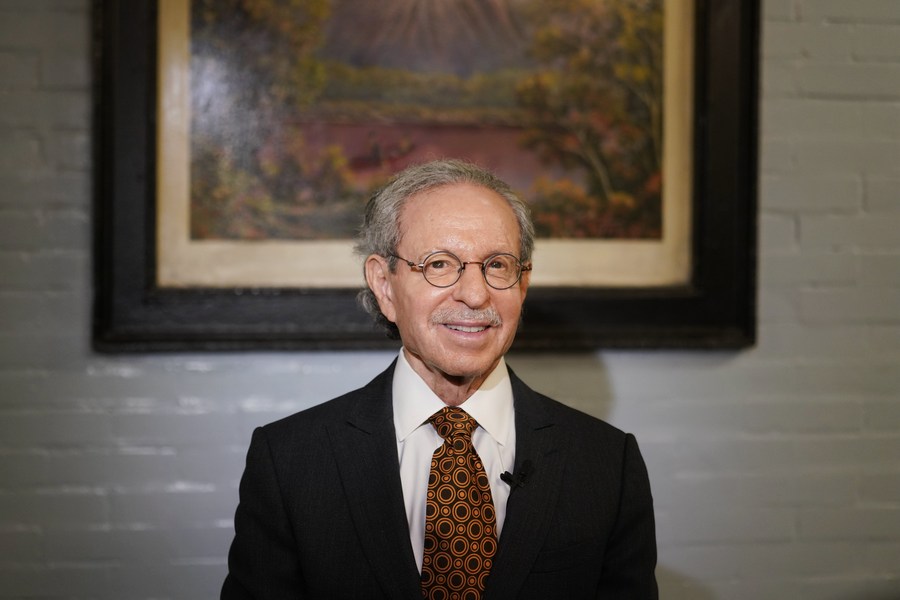

Robert Lawrence Kuhn, chairman of the Kuhn Foundation, speaks during an interview with Xinhua in New York, the United States, Sept. 17, 2023. (Xinhua/Wu Xiaoling)

Looking to the future, along with controlling and preventing risks, BRI projects will focus more on science and technology, and on industrial transformation, leveraging China's industrial and supply chain advantages.

y Robert Lawrence Kuhn

On the 10th anniversary of China's visionary Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), I offer a retrospective assessment and a prospective forecast.

Actually, I've been tracking the BRI literally from its start. I recall Sept. 7, 2013, when President Xi Jinping, standing at a lectern at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan, announced China's vision to build a "Silk Road Economic Belt" -- over land, across Eurasia, engaging Central Asia and linking with Europe. The next month, addressing the Indonesian Parliament, Xi proposed the "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" -- over water, China reaching out to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe. I spoke at the first two BRI conferences: 2014, in Urumqi, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, "The New Silk Road Economic Belt," and 2015, in Quanzhou, Fujian Province, "The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road."

The BRI has increasingly become a pillar of China's foreign policy. It leverages China's unequaled experience and competitive advantages in constructing infrastructure: rail, roads, ports, airports, power plants, and telecommunication. Nothing is more important for developing countries than infrastructure, and the foundation of all developmental economics is infrastructure.

Over the past ten years, China has signed more than 200 BRI cooperation documents with more than 150 countries and 30 international organizations, covering more than three quarters of the countries on earth. China has established more than 3,000 cooperation projects. Chinese goods flow to more than 300 ports.

According to a 2019 World Bank policy paper, the BRI is largely beneficial. First, global income will increase by 0.7 percent (in 2030 relative to the baseline), which will translate into almost half a trillion dollars in 2014 prices and market exchange rates. Second, globally, the BRI could help lift 7.6 million people out of extreme poverty and 32 million out of moderate poverty.

In a recent white paper, China says that, over the decade, "the country has contributed its strength to building a global community of shared future." In an authoritative retrospective, a deputy head of the National Development and Reform Commission, which oversees the BRI, wrote that the country adheres to "the principles of extensive consultation, joint contribution, and shared benefits" and to "the concepts of openness, greenness, and integrity, and aimed at high standards, sustainability, and benefiting people's livelihood." The BRI has a five-pronged approach: policy communication, infrastructure connectivity, unimpeded trade, capital financing, and people-to-people bonding.

Over the 10 years, China has constructed six major international economic corridors: New Eurasian Land Bridge, formed around the Trans-Eurasian international railway trunk line from China's Jiangsu Province to Rotterdam in the Netherlands; China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor; China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor, from China's Xinjiang via Central Asia to the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean and the Arabian Peninsula; China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, from Kashgar in Xinjiang, China, to Gwadar Port in Pakistan; Southwest Asia Continental Bridge, or the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor; and China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor, from southwest China's Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region to and through Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore.

Major projects: the just-opened Jakarta-Bandung line, Indonesia's first high-speed railway, branded "Whoosh"; Hungary-Serbia Railway; China-Laos Railway; and the Piraeus Port in Athens, Greece. The BRI's flagship project is the China-Europe freight trains, with 84 operating routes, reaching 211 cities in 25 European countries, promoting interconnection and enhancing trade all along the routes.

China's BRI is not charity. China says it seeks "win-win," which means that China wins too. China wins via preferential access to vast sources of raw materials (e.g., oil); substantial business for its massive, state-owned construction companies; developing new markets for its products to reduce trade dependence on the United States and Europe; and geopolitical support in the United Nations and elsewhere for contentious issues. China thinks very long term.

If I'd be telling a story that the BRI is all "roses and cheers," that the BRI sprouts no problems, then I'd be telling a falsehood. Challenges abound, including project delays, poor project selection, cultural clashes, terrorism, and pushback from Western countries. Yet, almost every developing country wants more, not less, of China's BRI. They need it.

That's why China is recognizing the challenges, hearing the criticisms, and making mid-course corrections. After galvanizing nearly a trillion dollars, and having established more than 3,000 cooperation projects, Beijing is working on a policy overhaul.

A slowing global economy, rising interest rates, and higher inflation, exacerbated by the pandemic and natural problems of new programs, have left developing countries struggling to service their debts. Some Western officials and media have accused China of deliberately structuring its lending practices to seize assets in a calculating "debt-trap diplomacy," a charge that Western analysts have debunked. In 2019, after reviewing 40 cases of China's external debt renegotiations, the Rhodium Group, a leading research provider, found that while debt renegotiations and distress among borrowing countries were common, asset seizures were a rare occurrence. Despite its economic weight, China's leverage in negotiations was limited.

In 2020, after some concerns and hesitations, China joined an international debt-relief effort, labeled the Common Framework and endorsed by the G20, that coordinates creditors in debt negotiations. A 2022 analysis from the Centre for Economic Policy Research found that China has become the most important official player in international sovereign debt renegotiations. Since 2008, Chinese creditors arranged at least 71 distressed debt restructurings -- more than three times the number of sovereign restructurings with private creditors, and higher than the total number of Paris Club restructurings. China's crisis resolution approach often requires serial debt restructurings.

Southeast Asia is central to China's BRI vision. Major projects include a 1,035-km high-speed railway in Laos; the just-opened 142-km; and the 665-km East Coast Rail Link project in Malaysia under construction.

This photo taken on Aug. 17, 2023 shows high-speed electrical multiple unit (EMU) trains of the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway in Bandung, Indonesia. (Xinhua/Xu Qin)

New methods of financing BRI projects, especially via the China-founded Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Silk Road Fund, bring world-class financial standards, including rigorous due diligence and sophisticated financing structures tailored for each project's projected cash flows.

Chinese officials are determined to learn lessons from early BRI projects to improve future BRI projects by tightening the selection process, making projects more productive, adjusting financial structures, making projects more conservative, and controlling diverse risks to make projects more viable. The only thing not subject to mid-course correction is President Xi Jinping's BRI vision itself, which he has called "a project of the century." Significantly, the BRI has been written into the Constitution of the Communist Party of China.

China's mid-course corrections focus on recognizing, assessing, managing, and preventing risks, including political uncertainty and deteriorating security conditions, with kidnapping and robbery, armed attacks, and terrorist attacks becoming more frequent. It also includes China's heightened sensitivities to local issues, such as cultural differences, including tensions between Chinese and local workers, and indigenous industrialization, especially helping host countries develop their own industries, so they do not feel they are inadvertently becoming dependent on China as a so-called "neocolonial" economic colony. BRI officials are admonished to conduct comprehensive risk assessments before "going global" and commencing projects: they must pre-set risk monitoring and control systems to achieve "early detection, early warning, and early prevention."

The BRI began as China's strategic vision to connect China with Europe through Central Asia. It then expanded to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Then to Latin America -- really to the entire developing world. Today, with its vast array of projects and activities, the BRI exemplifies China's global economic ambition and growing footprint. The BRI is even said to represent China's foreign policy, tasked to achieve strategic goals, such as internationalizing the renminbi and securing natural resources from oil for energy to lithium for batteries.

This photo taken on May 23, 2023 shows a platform of the Mombasa-Nairobi Railway in Nairobi, Kenya, a flagship project of China-Africa cooperation. (Xinhua/Wang Guansen)

Looking to the future, along with controlling and preventing risks, BRI projects will focus more on science and technology, and on industrial transformation, leveraging China's industrial and supply chain advantages. With its 41 major industrial categories, 207 intermediate categories, and 666 small categories, China is the only country in the world with all industrial categories in the United Nations Industrial Classification. Moreover, China's technologies are now world-class in new energy vehicles, high-speed rail, offshore engineering equipment, wind and photovoltaic power, and power transmission and transformation. These provide opportunities to achieve high-level industrial cooperation with BRI countries.

President Xi emphasizes that BRI projects should cultivate new growth areas such as health, green, and digital, promoting information sharing and capacity building in sustainable, low-carbon development. In digital, China calls for new business models of BRI cooperation: smart cities, Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and e-commerce. Mobile payments, where China is a leader, can spearhead "going global" and enhance the competitiveness of Silk Road e-commerce, and thus augment China's international influence. As BRI projects continue to develop, becoming more technological and more targeted, new business opportunities will emerge, especially for private companies.

To improve project quality, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), will work harder to secure financing. Today, China's policy banks are more risk-averse and SOEs must become more risk-sharing. A recent case is in Kenya, where the Chinese SOE built an expressway in Nairobi under a "public-private partnership" with the government.

It is estimated that in the next ten years, BRI countries will increase trade volume by 2.5 trillion U.S. dollars, boosting economic globalization and reducing global inequalities. It would also facilitate geostrategic re-alignment, reforming the international order. That's China's plan.

I look forward to continuing to track the BRI for another 10 years.

Editor's note: Robert Lawrence Kuhn, a public intellectual and international corporate strategist, won the China Reform Friendship Medal (2018). He is also chairman of the Kuhn Foundation.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Xinhua News Agency.■